Pas d’Armes and Late Medieval Chivalry: Tournament, Sport and Spectacle

Overview of the pas d'armes

Typical features of a pas d'armes

The pas d'armes could include elements from other forms of tournament, for example the traditional joust and mêlée (i.e. pitched battle, known as a tourney if taking place within closed lists). These combats could therefore be on either foot or horseback and participants could use a range of different weapons. The pas d’armes also shared some general features with these two other types of tournament: it was witnessed by an audience that could comprise both nobles and non-nobles, women and men; and, though it was often held in an urban setting, it could sometimes be organised in or near a castle or in the countryside near a bridge.

Even more than these other two tournament forms, however, the pas d'armes was purposely designed to be very spectacular and was particularly popular in the fifteenth century. It can also be distinguished from them in more specific ways in generally combining the following key features:

- The person organising the event, known as the entrepreneur, alone (or together with other knights and squires) defends either a passage (such as a bridge or a gate) or a symbolic object (such as a fountain or a column) against all challengers;

- This defence is conducted according to a fixed set of rules called 'chapters of arms' which were circulated by the entrepreneur beforehand;

- It involves a theatrical production and/or a fictional scenario often inspired by imaginative literature such as romances.

Inspirations

The term pas itself may have come from a legend attached to the Third Crusade (1189-92) about how the French king, Philippe Auguste, with a group of twelve knights that included the English king, Richard I, succeeded in defending a narrow passage near Jerusalem against the great Muslim leader, Saladin. This legend was written up in a 13th-century text called the Pas Saladin.

Historical pas d'armes may also have been inspired by earlier tournaments, such as those at Le Hem (1278) and Chauvency (1285) in northern France, which involved knights adopting the names and coats of arms of knights associated with King Arthur's court such as Lancelot or Gawain, this literary matter being immensely popular all over Europe. Some earlier tournaments even referred to themselves explicitly as 'Round Tables' in homage to this literary tradition.

Many French romances also inspired historical pas d'armes directly, whether they featured Arthurian knights or those presented as pseudo-historical figures such as the Greek hero Florimont (late 12th century) or the Galician hero Ponthus (late 14th century). Ponthus, for example, organises a ritualised combat that is a pas d'armes in all but name in the forest of Broceliande in Brittany. As 'The Sorrowing Black Knight of the White Arms', he defends a fountain against four knights a month for a whole year, all for love of his lady, the fair Sidoine, daughter of the Breton king. These three scenes from an illuminated manuscript of the romance of Ponthus et Sidoine show (from left to right): the arrival of a first group of four challengers; a combat between Ponthus and an opponent; and the post-combat festivities in the presence of Sidoine and her father (London, British Library, Royal 15 E VI, fols 213r, 213v, 215r. Photos: BL).

The arrival of a first group of four challengers.

A combat between Ponthus and an opponent.

The post-combat festivities in the presence of Sidoine and her father.

Locations

The first pas d'armes took place under the aegis of royal courts in Castille and Aragon in the first third of the fifteenth century; they were then staged under the authority of the ducal courts of Anjou and Burgundy from the mid-1440s for several decades and they remained popular in northern France well into the first third of the sixteenth century. Whilst pas d'armes never seem to have been organised within the orbit of royal courts such as England and those in the German-speaking courts of Cleves or Habsburg, recent research has shown that they were held in the French- and Italian-speaking duchy of Savoy and even at the royal court of Scotland in the early 1500s.

Motivations

The fictional scenarios that often accompanied the advance proclamation of a pas d'armes by a herald travelling from court to court, present the knight-entrepreneur as obeying the wishes of a lady or as acting to defend her. In the Pas du Perron Fée (Bruges, 1463) for example, the knight, Philippe de Lalaing, claims that he has been taken prisoner by the 'Dame du Perron Fée' who demands that he fight so as to obtain his freedom.

In reality, a knight had many different reasons for organising one of these events:

- to allow existing tensions between different factions at the same court or between members of neighbouring courts to be expressed within the regulated confines of a tournament, rather than in open warfare, as at the Paso Honroso (Órbigo Bridge, León, 1434) which pitted Castilians against Catalans and Aragonese knights;

- to enhance his noble status and standing at a ducal or royal court by demonstrating his military prowess and earning membership of a chivalric order such as the Order of the Golden Fleece in Burgundy (this may have been Philippe de Lalaing's real aim);

- to help build cohesion in a group of knights belonging to a particular court in preparation for future military campaigns, such as the Pas des armes de Sandricourt (1493), which brought together knights who would fight in King Charles VIII of France's bid to invade Italy in 1494;

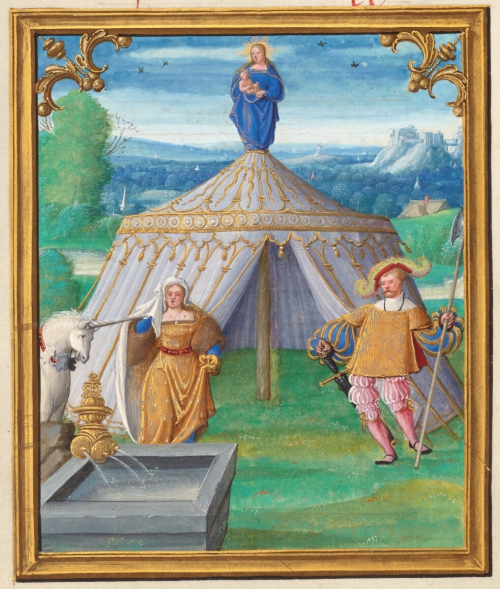

- to drum up support for a crusade, as at the Pas de la Fontaine des Pleurs (Chalon-sur-Saône, 1499-50, see picture above) where the entrepreneur, Jacques de Lalaing, claimed to be fighting for the 'Dame des Pleurs', an allegorical representation of the beset Church in the Holy Land.