Pas d’Armes and Late Medieval Chivalry: Tournament, Sport and Spectacle

Preparing for the event

Permission and proclamation

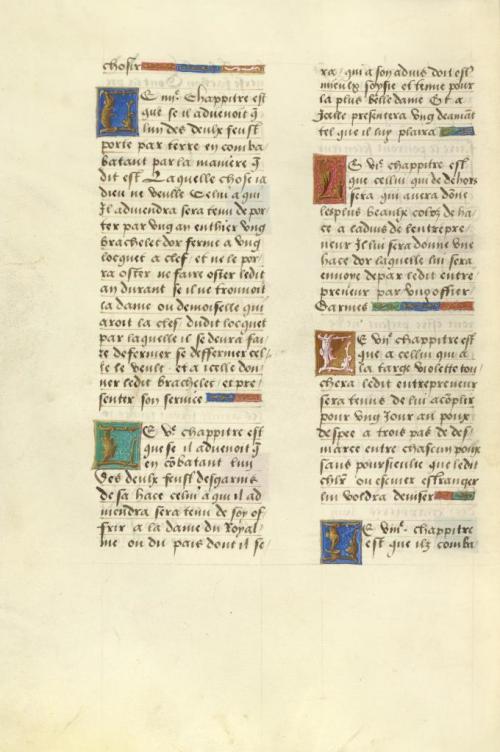

Before holding a pas d'armes, the would-be entrepreneur would first have to obtain permission from his lord, prince or king to do so; a date and suitable venue would then be agreed upon. Once this permission was granted, the entrepreneur would engage the services of a herald to write up a letter of challenge (often with a fictional scenario explaining the knight's motivation) and the 'chapters of arms' that outlined the rules of engagement to be followed.

The herald would then take these documents all over a particular territory or into several territories and proclaim them publicly so as to attract challengers to come and take part in the event. Would-be challengers would have to obtain permission from their own lord, prince or king to be allowed to compete.

A challenger would then either come in person or send a herald on his behalf to declare his intention to compete at the pas; this would involve either sending his shield with his coat of arms or striking a shield attached to a tree or a column by the entrepreneur. This committed him to taking part in the event, much like a legal contract.

Rules of engagement

Rules were indispensable given that a man's honour was at stake and the passions involved in any form of armed combat between two noblemen always potentially ran the risk of degenerating into a private quarrel that could then embroil whole families in a feud. The need to establish ethical fair play and equality between opponents is thus central to these chapters of arms which typically stipulate the following:

- the need for all competitors to prove their noble lineage (usually on both the maternal and paternal sides) so as to be allowed to take part;

- the need for all competitors to stop fighting when told to do so by the judges;

- which weapons were to be used in any particular event (either sharpened or rebated, and supplied by the entrepreneur with the challenger having first pick);

- how many blows/strokes with sword or pollaxe were to be exchanged or courses with lances run (either decreed by the entrepreneur or left up to the challenger to decide);

- what types of armour/harness (single or double) or saddles (those used for war or those for jousting) were permitted;

- what forfeits were to be imposed in the event of one competitor gaining a particular advantage over another (through unhorsing him or causing him to drop his weapon and/or fall to the ground);

- whether or not it was permissible for a challenger to watch the entrepreneur fight before his own bout was due, and so on...

Click here to read a translated extract from the chapters of arms of the Pas de l'Arbre Charlemagne (Marsannay-la-Côte, 1443), as drawn up by the entrepreneur, Pierre de Bauffremont, lord of Charny.

Paying the bills

Only a really wealthy knight could afford to put on a pas d'armes, but he might receive a contribution to his costs from his lord. Louis de Hédouville, the chief entrepreneur of the Pas des armes de Sandricourt (1493) which was held at his own castle, received some money from King Charles VIII of France, but he still spent a fortune accommodating and feeding 1800-2000 people for five full days at a cost of 400-500 francs per day. This is an enormous sum if we compare it with the annual wages given at the time by the king to one of his best armourers, these being 240 livres tournois (one franc roughly equals one livre tournois).

For other entrepreneurs, the staging of a pas d'armes in an urban setting was more like hosting a modern World Cup or Olympic Games. Towns would often compete to hold one since there were huge economic benefits to be had from attracting wealthy competitors needing arms, armour and clothing as well as hundreds of people wanting to spectate, all of whom also needed accommodation, food and drink for several days or weeks at a time, with some events running for several days a month over a whole year. Financial accounts from princely households and towns survive for some pas d'armes. From these, we can deduce the costs involved in preparing a suitable playing surface for combat, building lists and pavilions for the competitors, erecting stands for judges, heralds and high-ranking guests, and even creating pieces of ephemeral architecture such as a huge column or a castle in order to depict the fictional scenario.

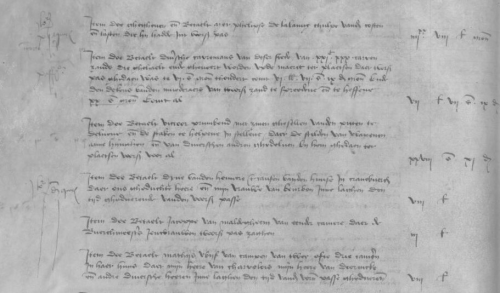

The town accounts of Bruges detail the costs of staging the Pas du Perron Fée which was held on the main Market Square in May 1463. Many of these costs concern the conversion of the paved square into a jousting arena where safety and jousting fences were put up and the horses would not slip. Other costs concern payments to the entrepreneur of the pas, Philippe de Lalaing, and his lord, Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy and count of Flanders:

- 'two fences on the market square for jousting: 2 lb. gr.'

- '1,000 bundles of straw to spread over the jousting surface: 6 s. 8 d.’

- ‘to several carters of this town for 2,130 cartloads of sand which were brought and taken to the market square where the pas was held: 6 lb. 7 s. 9 d. gr.'

- 'for two or three rooms where my lord of Charolais, my lord of Tournai and several other gentlemen were lodged during the time of the said pas: 8 lb. gr.'

- 'to Philippe de Lalaing, to help him to bear his costs and expenditure: 88 lb. gr.’

- ‘to Duke Philip the Good for giving his consent to hold the pas here in the town in his presence, where many other lords of his kin and other notable people were present, the sum of 400 lb. gr.’

As a chamberlain in the service of Duke Philip the Good, Philippe de Lalaing could expect a wage of 6 lb. gr. per month. This means that the sum he received from the town came to almost 15 times his normal monthly wages. However, a master craftsman had to work almost 100 months to earn the same amount of money as Philippe did on that one occasion!