Bruges, 3 July 1468: in one of the richest and most powerful cities of Flanders, hundreds of people have gathered to celebrate the wedding of Charles the Bold, the mighty duke of Burgundy, and Margaret of York, the sister of Edward IV, the English king. But now extraordinary things are happening on the marketplace. A golden tree stands in its centre, surrounded by three people: a dwarf with an hourglass, a giant and a nobleman. A herald announces the imminent arrival of his lord, Adolf of Cleves, who wishes to challenge the ‘Knight of the Golden Tree’. This knight is none other than Antoine, the ‘Great Bastard of Burgundy’, Charles the Bold’s half-brother. Today, he has assumed the identity of the ‘Knight of the Golden Tree’ in order to fight anyone who comes to challenge him. Adolf was the first of twenty-six competitors to do so...

So what was going on here?

The ‘Golden Tree’ at Bruges was an example of a pas d’armes, a type of chivalric tournament inspired by themes from courtly literature. At this event in 1468, the town marketplace became a lavishly decorated stage, with stands covered in rich tapestries for the judges and onlookers to sit in. An entire court, its visitors and the citizens of Bruges were all there to watch noblemen fight to acquire honour, reputation and wealth and to demonstrate their worth and masculine prowess. Yet this was no mere theatrics as the risk of injury was very real...

The pas d’armes is much less well-known now than other forms of tournament such as mêlées (pitched battles) or single combat in the lists, but in its own day it had a fascination and a glamour that were unrivalled. The pas d'armes in fact could include elements from these other forms of tournament. The combats, for example, could be on either foot or horseback and participants could use a range of different weapons. The pas d’armes also shared some general features with these two other types of tournament: it was witnessed by an audience that could comprise both nobles and non-nobles, women and men; and, though it was often held in an urban setting, it could sometimes be organised in or near a castle or in the countryside near a bridge.

More than these other two tournament forms, however, the pas d'armes was purposely designed to be spectacular and was particularly popular in the fifteenth century. It can also be distinguished from them in more specific ways by having some or all of the following key features:

- It is organised by a knight or squire known as an entrepreneur;

- This entrepreneur alone (or together with other knights and squires) defends either a passage (such as a bridge or a gate) or a symbolic object (such as a fountain or a column) against all challengers;

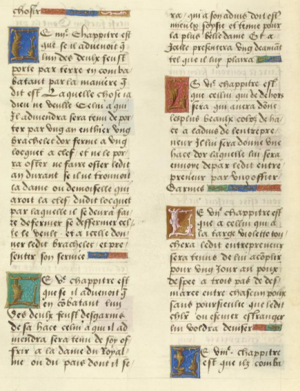

- This defence is conducted according to a fixed set of rules called 'chapters of arms' which were circulated beforehand;

- It involves a theatrical production and/or a fictional scenario often inspired by imaginative literature such as romances.

The theatrical frameworks and mechanisms of challenges were described in detailed specifications known as chapitres (chapters of arms) while judgements on the various encounters were recorded by heralds for posterity, along with descriptions of the many banquets, dances and theatrical entremets (interludes) that formed an essential part of the post-combat entertainments.

The pas d’armes was not just a sporting event but also a political, social, and artistic performance and a multi-media spectacle. It was an activity designed to hone chivalric prowess in times of peace and to provide training in preparation for times of war; it could also foster diplomatic relations between an international brotherhood of knights and their sovereign lords. These combats, a number of which, particularly in the Burgundian lands, were staged in an urban environment, could likewise mediate relations between the different social groups who exercised power in the polity; their elaborate staging and symbolism could similarly be an expression of aspiration and encouragement to crusade. In addition, they promoted a form of aristocratic masculine identity that was both homosocial, in terms of the bonds they fostered between competing knights, and heterosexual, in positioning ladies as admiring and appreciative spectators of these knights’ feats of arms, as amorous inspirers of chivalric prowess, and as participants in post-combat rituals.